But this year, in Houston ISD, a handful of students are opting out: A cadre of parents has joined a growing national backlash against high-stakes testing, a system they say is strangling the education it is supposed to help.

Can Houston parents say no to state-required tests?: In Montrose, a handful of families are opting out of the STAAR

By Claudia Kolker, for the Houston Chronicle

March 31, 2015 Updated: April 1, 2015 11:14am

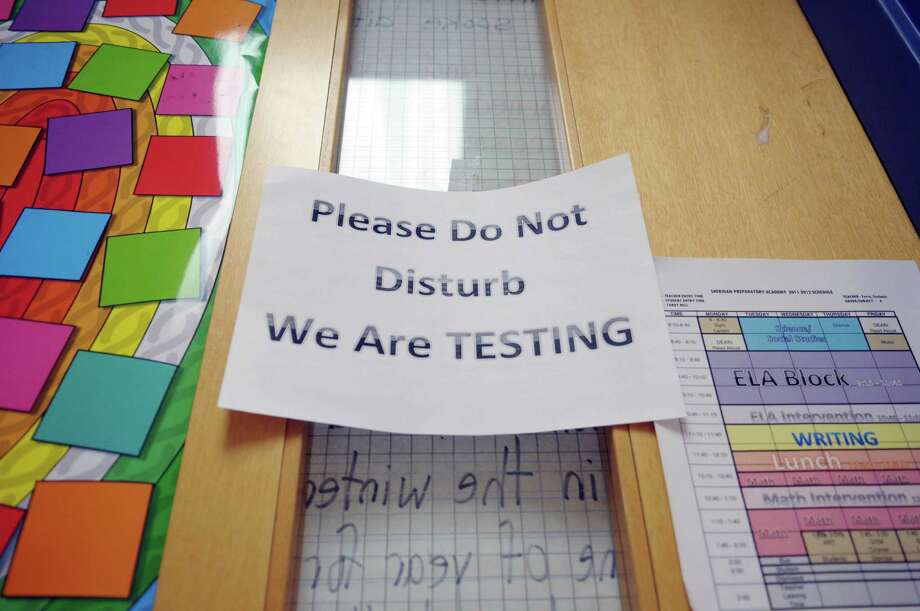

This week, in public schools across Texas, testing season began again: the familiar and, for many, unhappy ritual of hushed campuses, cardboard isolation screens, and silent filling-in of bubbles on standardized test forms.

But this year, in Houston ISD, a handful of students are opting out: A cadre of parents has joined a growing national backlash against high-stakes testing, a system they say is strangling the education it is supposed to help. To date, only one Houston Independent School District student is known to have opted out of the standardized testing. This spring, the number has multiplied, with as many as a half dozen parents in the Montrose area alone saying that they planned to pull their children out of the state-mandated test.

But keeping children home rather than letting them take the STAAR (State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness) achievement tests at school is not an easy decision. It could, administrators say, be fraught with peril: not just for the students' chance at promotion to the next grade, but for their teachers and schools as well.

One of those parents is Christine Cullen, mother of an elementary student at Wharton Dual Language Academy. Cullen worries what her opting out will mean not just for her daughter, but for the teacher that Cullen's whole family has grown to admire.

During the first weeks of the school year, Cullen recalls, the young instructor spotted her daughter's shyness, seeing that she did well on tests but was reluctant to speak up. So at stray moments, in a dozen small ways, the teacher made it a project to feed the little girl's confidence. Seven months later, Cullen's daughter giggles with friends in class and weighs in stoutly during discussions.

"That,'' Cullen says, ''is a passionate teacher.''

Now she fears that she may be derailing that teacher's career. Cullen worries that by opting her high-scoring child out of this year's STAAR, she may be damaging her teacher's test score average, thereby damaging her chances of a positive performance review.

State law does not allow opting out. Passing STAAR tests is required for graduation from high school. And for all grades, Section 26.010 of the Texas education code prohibits parents from removing children from school "to avoid a test."

"We do not seem to have a lot of parents opting out," Houston ISD spokesperson Ashley Anthony said on Tuesday. It's more common, she said, in suburban districts.

If a student does not take part in testing, HISD is still required to submit a blank, scorable answer sheet on the student's behalf. What the impact of that blank sheet would be on student, teacher, and school is not clear.

TWENTY YEARS ago, Texas' testing system was seen as a beacon. The state had routinely ranked second to last in national educational outcomes, and when those shortcomings began to drive off new investors in the state, then Governor George Bush and the business community launched a push for early reading and student assessment. Social promotion, which had often papered over the needs of vulnerable students, was slowed. The resulting system in Texas, wrote the New York Times, was ''an emerging model of equity, progress, and accountability.''

When Bush was elected president, his No Child Left Behind initiative helped establish annual benchmarks for the whole country, to be measured by standardized tests from grades three through eight. Early on, some researchers claimed that the apparent success in Texas had been the result of artificially generated test scores that did not reflect real gains in academic quality. Within a few years, many educators and parents had soured on the system.

In places such as Harris County, the tests are now used for more than simply assessing student progress. They are used to grade, and reward or punish, educators and schools themselves. The STAAR, meanwhile, helps determine whether students can go to the next grade.

Isolated behind anti-cheating cardboard blinders, students are tested for four hours per day for each STAAR assessment. They sit in total silence, reading and snacks forbidden. To prepare, they spend additional instruction hours on practice tests, test-based homework, and drilling. HISD fourth graders take between 34 and 40 hours of practice tests, in addition to the actual STAAR and Iowa tests.

Across the country, families in less extreme testing environments already are pushing back. According to Community Voices for Public Education (CVPE), a coalition that backs low-stakes testing used only for diagnostic purposes, last year in New York more than 50,000 students opted out of at least one standardized test, and in Colorado, 17 percent of high school seniors boycotted new state tests. This spring, several hundred New Mexico high school students walked out of school in opt-out protests.

But in HISD, just one parent publicly opted out last year. Though she was told her third grader would suffer no consequences, mother Claudia de Leon Geisler later learned that her son's missing test scores could block his passage to fourth grade unless he attended summer school. After negotiations with the district, the family worked with the child on a week-long project instead.

''Everybody's scared and everybody's worried,'' says the mother of a fourth-grade student. She is one of at least six parents of Montrose elementary-school-age children who say they plan to opt out. Like other parents interviewed for this story, she asked that details of her child's identity be withheld. ''We needed to find out how it would affect our child, her teacher, and her school if we opted out and our high-performing child didn't provide them with test scores," the mother says. "Would it affect school funding? Would it affect teacher performance reviews? Our teacher is spectacular. We want to protect her.''

Three days before the first STAAR test, the family still didn't have answers. ''I'm not against testing,'' the mother, a former teacher, says. ''But it should be diagnostic, not high-stakes. The amount of time, and the weight, given these tests, is absurd and really stressful for our kids. My main concern is that I'm spending my tax money for my child to go to school and spend the majority of her learning time prepping for a test. These are her years for investigating the world.''

A TEACHER at a Montrose elementary school is refusing to administer the test for the same reasons.

''Before moving to Houston I taught in a private school,'' says the teacher, who asked that both she and her school not be named. When she first arrived in Houston, she says, she taught at an HISD school outside Montrose, and was horrified by her first glimpse of test culture.

"It was not teaching, it was not learning," she says. "It created an abusive environment for everyone: children, teachers, administration.'' She moved to her current teaching position in Montrose with the idea of eventually starting her own school, and was delighted by the humane environment she found. Until, that is, this February, when she had to administer the DLA, a STAAR length practice test required by the district.

''You have to understand: the school shuts down,'' the teacher says. ''There is no teaching. There is no learning. I had to sit there and force fourth grade kids to take four-hour long tests, and do it the next day and the next day, and act to them like it was a totally normal thing. It made me feel like a hypocrite. I was implying to the kids that this is something I believe in.''

Worse, she says, even when the testing is done a corrosive effect on learning continues.

"Once the testing was over last year, I thought, I'll actually be able to teach my kids something," the teacher remembers. "I passed out a story, we read it as a class, and the next day I passed out a quiz. One of my students raised her hand and said, 'I don't get it – isn't there multiple choice?' She didn't know what to do when it wasn't multiple choice and the answers weren't provided. I don't feel that my kids understood what learning was.''

The teacher has decided to leave HISD at the end of this school year. But first, she told her principal, she was going to protest.

''All I will say is that my principal was as understanding as he or she could possibly be,'' the teacher says. Instead of administering the exam, the teacher will take personal days during the testing period, offering volunteer enrichment education for students who are opting out.

Like many parents, though, the teacher broods about the wellbeing of her colleagues. "Unfortunately I can't make as public a statement as I want to,'' she says. "Test culture is a culture of fear. Everybody is terrified. Nobody knows what the consequences of their actions are going to be.''

FOR CHRISTINE Cullen, what began as concern for her child has morphed into something bigger.

''It began with the stress I saw our daughter experience,'' she says. ''But what got us to opt out waslearning how much money is being spent, where it is going, and how it is part of the privatizing of public education with no transparency, no independent oversight. That is what has triggered our family's desire to use opting out to civilly disobey.''

These tests were never designed to determine teacher pay or performance, says Linda McSpadden McNeil, director of the Center for Education and a professor of education at Rice University. McNeil is author of Contradictions of School Reform: Educational Costs of Standardized Testing.

According to McNeil, Texas paid nearly half a billion dollars between 2010 and 2015 to Pearson, the firm that develops STAAR, scores it, and verifies its validity. School districts across the state also spent as much as $500 million during that time for preparation materials, practice test drills, and test score reporting.

Yet the tests may not even reflect the performance of a school or teacher, says McNeil. More than 20 years of research concurs that the most consistent factor in a child's test-taking performance is family environment and socio-economic status. In other words, drilling, practicing, and ''teaching to the test'' tend to have little impact on a child's success in test taking.

Teacher assessment by professional peers and independent groups, and devoting more resources to children's health and home environments, would be far more effective at helping children learn, she says, as would replacing time spent on practicing for tests with time spent on substantive teaching.

''These tests were never designed as tools to reward or punish teachers,'' McNeil says. "To use diagnostic tests this way, for a purpose other than the one for which they were designed, is unethical.''

In fact, in a 2008 study, McNeil and colleagues found that high-stakes testing actually aggravates the dropout level for low-income students. Pressure to keep school scores high, the data showed, ''put our most vulnerable youth, the poor, the English language learners, and African American and Latino children, at risk of being pushed out of their schools so the school ratings can show 'measurable improvement.'"

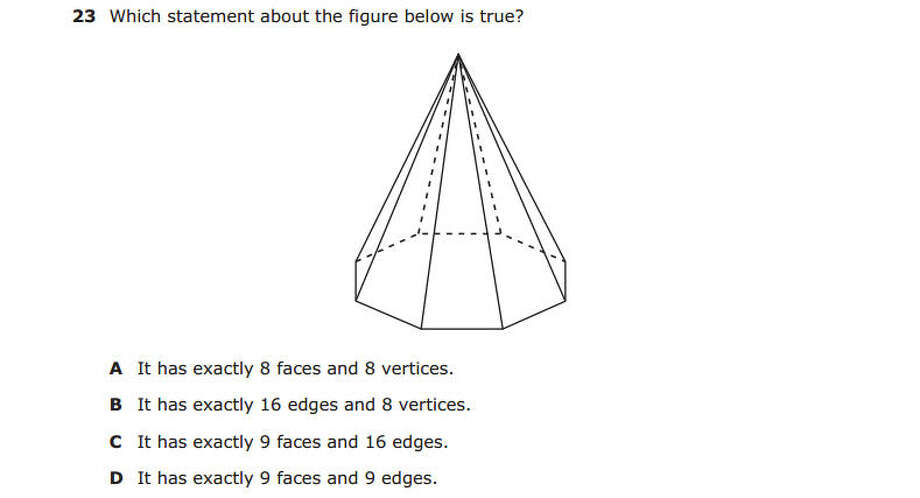

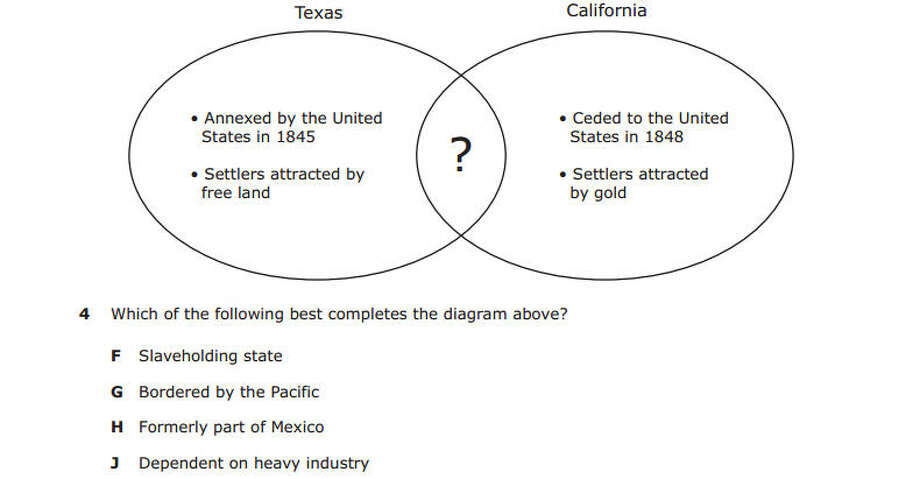

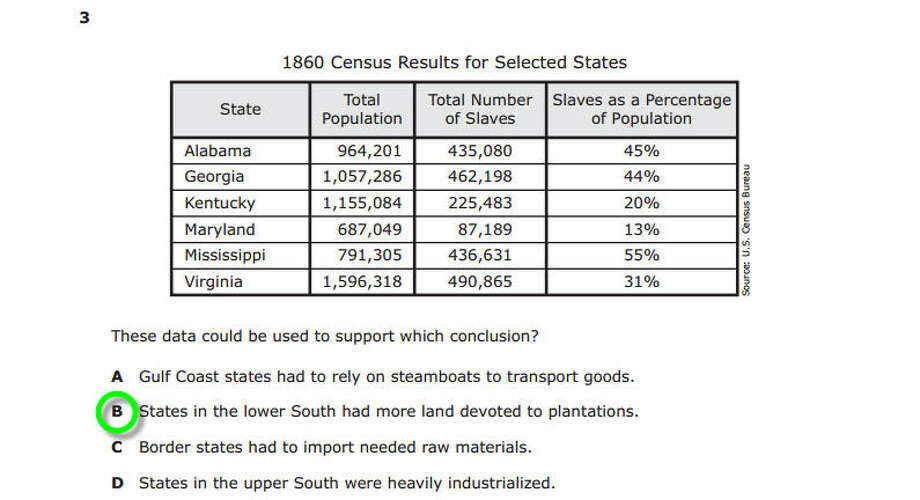

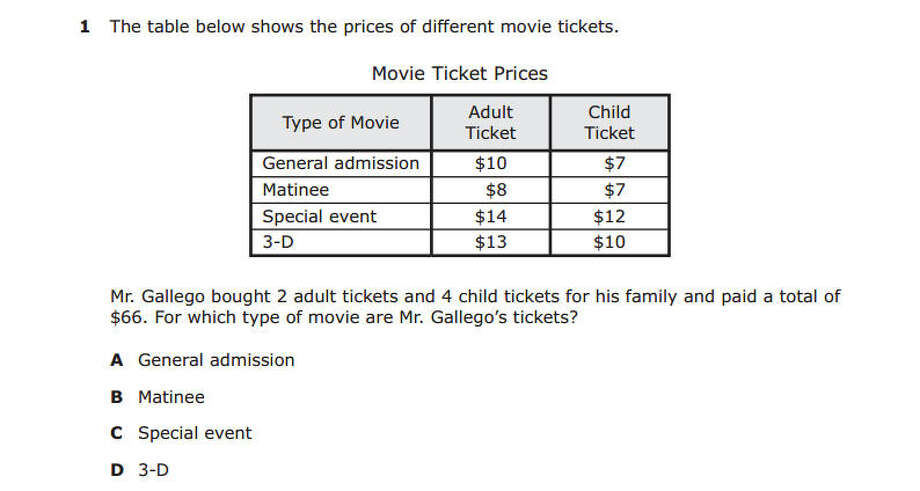

Question from the fifth grade math section of the STAAR.

STRESSING THAT each parent must make the testing choice best for his or her child, McNeil praised the Montrose parents' opting out as a way to challenge the system overall.

''Debating high-stakes testing only from the margins reinforces the system,'' McNeil says. "These parents who are taking action are making the real difference by not letting their children become mere data points in the accountability system."

This week, as the first STAAR test is passed out at Montrose schools, Christine Cullen says she feels encouraged by the information she's gathered from O'Neil and from CVPE.

She still worries about harming the teacher and school community to which she's so grateful. Nevertheless, Cullen feels clear, the choice has to be made.

"I feel blackmailed by this system," she says. "If we don't comply, the system could hurt not only our child, but also her teacher and our school. At a certain point, noncompliance becomes the only way to fight.''

Claudia Kolker, a staff writer for the Montrose District, is the author of The Immigrant Advantage: What We Can Learn from Newcomers to America about Health, Happiness and Hope. She is the mother of two HISD students who will not take STAAR tests this week.

Bookmark Gray Matters. It's diagnostic, not high-stakes.

Do you like this page?